Pacific Golden-Plover

General Description

Pacific Golden-Plovers have dark brown upperparts, spangled with gold to pale yellow or white. A white stripe extends from the forehead, over the eyes, to the wings. Breeding males are solid black from chin to under-tail coverts. Females are duller in color. They are similar in appearance to American Golden-Plovers, but have shorter wings, brighter yellow markings on their upperparts, and mostly white under-tail coverts and sides. Non-breeding adults have yellow-edged upperparts and yellowish heads and necks. Juveniles have a golden cast to head and neck and spotted upperparts. Distinction between these two species is not easy. Be sure to consult a good field guide.

Habitat

Migrating Pacific Golden-Plovers are typically found in coastal habitats such as mudflats, estuaries, and open ocean beaches. They nest on Arctic and subarctic Alaskan tundra, and may winter on islands in the Pacific Ocean as far south as Australia. Others go no farther for the winter than California beaches.

Behavior

Pacific Golden-Plovers are territorial on breeding grounds, and some individuals defend feeding territories on wintering grounds. They are swift in flight, but are more commonly seen roosting or foraging on the ground. Pacific Golden-Plovers spread out while foraging. They are visual foragers and feed by running and seizing prey.

Diet

Pacific Golden-Plovers feed on a variety of invertebrates such as mollusks, crustaceans, and insects. They also eat berries, leaves, seeds, and occasionally small vertebrates.

Nesting

Males may begin territorial display flights the day of arrival on tundra nesting grounds. Pairs form within a few days. The male builds a shallow scrape nest lined with lichen in sites with more vegetation than those chosen by American Golden-Plovers. The female lays four eggs, and both parents incubate. The male usually incubates during the day, the female at night. Chicks are precocial and can feed themselves within a few hours of hatching. Both parents tend the young. Pacific Golden-Plovers have one brood per season.

Migration Status

Pacific Golden-Plovers may cover 2,000 miles in a single nonstop flight from Alaska to the Pacific Islands, or they may stop along the way. Pacific Golden-Plovers and American Golden-Plovers overlap in time and location during migration, but Pacifics tend to migrate later. Spring migration takes place mainly in April and May, and fall migration lasts from August through October. A few individuals may not migrate.

Conservation Status

Pacific Golden-Plovers were hunted in Hawaii until 1941, but with subsequent protection, populations have recovered. Pacific Golden-Plovers do not appear to be threatened at this time, although commercialized exploitation and habitat loss still occur in parts of their winter range.

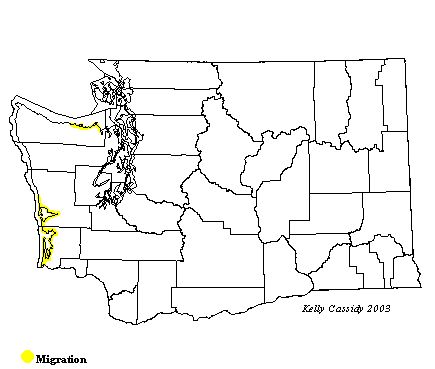

When and Where to Find in Washington

These plovers are found mostly on the outer coast. A few may be found on the outer coast in the spring. During the fall, flocks are seen regularly along the coast near Grays Harbor and Leadbetter Point. Pacific Golden-Plovers may be more common than American Golden-Plovers on the Washington coast.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | U | U | U | R | |||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | |||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Black-bellied PloverPluvialis squatarola

Black-bellied PloverPluvialis squatarola American Golden-PloverPluvialis dominica

American Golden-PloverPluvialis dominica Pacific Golden-PloverPluvialis fulva

Pacific Golden-PloverPluvialis fulva Snowy PloverCharadrius alexandrinus

Snowy PloverCharadrius alexandrinus Semipalmated PloverCharadrius semipalmatus

Semipalmated PloverCharadrius semipalmatus Piping PloverCharadrius melodus

Piping PloverCharadrius melodus KilldeerCharadrius vociferus

KilldeerCharadrius vociferus Mountain PloverCharadrius montanus

Mountain PloverCharadrius montanus Eurasian DotterelCharadrius morinellus

Eurasian DotterelCharadrius morinellus